This is an age which seems special in a particular sense. It appears that atheism, especially in the Western societies, has become popular enough to be considered a mainstream belief structure, rivaling the popularity of traditional religions. I don't think this was nearly the case even in the last generation in the West, just like it is not so currently in India. However, I am quite certain that the Indian society would also move away from religion just like the rest of the world seems to be doing. This superficial departure from the traditional belief systems will neither abate nor diminish and we are most certainly moving towards a world where less and less people will believe in a God. At this point when atheism is becoming increasingly mainstream, it is rather interesting to consider the following question: where is the catch in all this? Because there must be a catch. So many people, when thinking alike, must necessarily be shortsighted. Massive herds of people, united in a single belief system, share one characteristic across historical lines: an appalling lack of intelligence.

I have come across my share of religious people and atheists and I find it interesting that those who believe almost always appear better socially adjusted, less materialistic, and happier with their circumstances. The fashionable atheists, on the other hand, generally come out bitter, cynical, and not necessarily any more intelligent than the religious group. The atheists seem to be well versed in the latest scientific developments and they use each new one to point out to the religious people why they must be wrong. This constant pestering, of course, makes them absolutely insufferable human beings. Moreover, it is clear that their scientific knowledge is nothing more than a very neatly arranged docket of facts and doesn't amount to any real understanding of important issues which must surface when one removes a God from the picture. They have killed off the entity which provided meaning to the lives of humans and have tried to replace it with vague and pathetic evolutionary explanations. What they have actually replaced God with is not any acceptable explanation but with an utter obsession with materialism. The central problem of life is finding something which would keep one distracted from the eternal oblivion and meaninglessness which awaits us all. God is a great fictional character which fits the bill perfectly. However, there are other ways to distract ourselves in this life. They include obsessions with power, money, success, fame, fitness, sports, health and others. The general trick is to keep fretting about the small and unimportant things in life to the extent that one doesn't have time to think about the important questions and this is what God really has been replaced with. A simple obsession with crass materialism with all its moorings and pitfalls and this is the catch with the fashionable atheists of the present. They are right in understanding the fictional nature of God but they have nothing appropriate to replace the idea with. Perhaps there exist no adequate replacement. At least, I am not intelligent enough to figure it out.

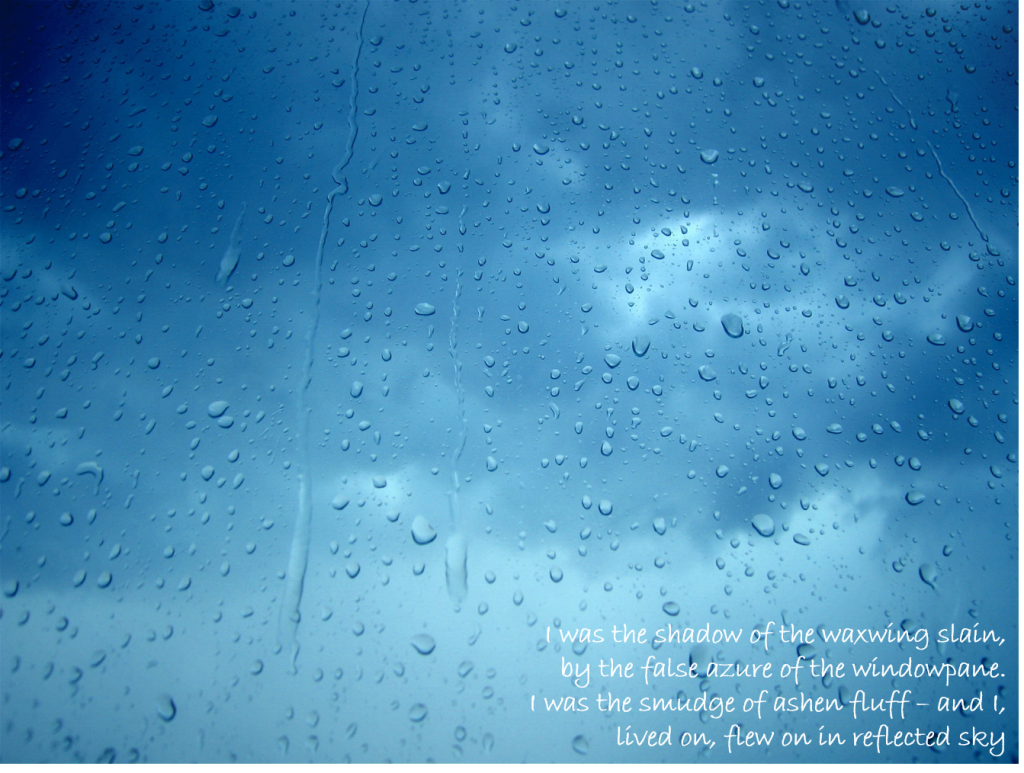

Reminds me of the following by Nietzsche (parable of the madman):