Category Archive: Philosophy

Pale Blue Dot

Posted by Ankit On April 10th, 2010

Chicken...

Posted by Ankit On April 6th, 2010

...or Buffalo wings, as they are called in the country for which the rest of the world is an appendix, refers to the uncooked lump of meat skewered over the top of two drumsticks. Sure it has two eyes, a nose, and two ears but these are details not worth the time of anyone except the technical ones - and let's face it, their opinions don't count. So anyhoo, I was describing Chicken. Well, not much to describe there, is it? They go about their lives doing something quite inconsequential until one day - BAM - on a barbeque, roasting away under the warm embrace of Lawry's garlic salt. Some of them give eggs, a lot of which end up in Denny's and the rest of them produce more chickens which send up Lawry's share by a fraction of a percentage. So if there is like a chicken equivalent of Immanuel Kant who has brooded upon the purpose of his life, I suspect that Lawry's pvt. ltd. features prominently in his musings. If eggs have life (you never know, some people even think plants have life!), they probably think about Denny's a lot. But I think we should really rein in our crazy speculations, which already crossed the line of rationality when we started thinking of chickens and eggs as anything more than food. What a crazy idea! Anyhoo, to make things a bit clearer, because let's face it - it's a complicated topic, I have made the following flowcharts which explain everything about chickens and eggs:

1 Chicken -> 2 drumsticks + 1 barbecued breast piece

1 egg -> not much, but 2 eggs -> 1 omlette

Speaking of chickens and eggs, I have often wondered which came first. I think we'll have to see if Lawry's setup their shop before Denny's because let's face it, what would Lawry's have made if the world only consisted of eggs? Vice-versa, how would Denny's have made omlettes from chickens? A quick search shows that Lawry's was established in 1938 and Denny's in 1953 which means there were no chickens before 1938 and no eggs before 1953. There you have it - once and for all, a huge conundrumstick solved!

God and Russian literature

Posted by Ankit On February 26th, 2010

We all understand that it's all a theater, don't we? That the world as we know it is just a cosmic afterthought, a mere divine joke in which a lot of people take their parts far too seriously and the rest of them have a hearty laugh about it. It's like a friendly banter over beer and you just have to look closely enough to realize that nothing really is sacrosanct. So in this world which appears serious but is actually quite ridiculous, every smart theory must have its stupid, trivial dual. Like god for example. Science works its ass off trying to explain every little detail, checks and rechecks itself innumerable number of times, sweats like a pig, and finally has to contend with so much uncertainty that Heisenberg's cat, in comparison, seems like a sure bet. It's the serious explanation but then there's the joker's explanation which is god. 'It's just the way it was intended' and poof!, there goes all your seriousness.

Anyway, the reason I was thinking on these lines is that while reading a bit of Dostoevsky, it suddenly dawned upon me that all my disappointment in Russian literature might not have anything to do with its content at all. One thing is for sure though, when it comes to depressing, morbid imagination there is no race which trumps the Russian. No other group of people, as a whole, has inflicted as much misery upon the world as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov together have through their stories of the sad farmer whose wife had an affair. But that is probably not the only reason why I find it hard to read Russian literature (actually I very much like Chekhov). The main reason, I think, is the bloody names these Russians have. 'Bezukhovs', 'Drubetskoys', 'Ekaterina Alexandrovna Shcherbatskaya', 'Pavel Fyodorovich Smerdyakov', 'Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtseva' etc. I mean, what the hell? Here I am, trying to wade through an already dense plot where commentaries on human nature are getting intermingled with moral dilemmas and plot twists, and suddenly Ms. Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtseva walks in and I have to spend the next two minutes dealing with her roadblock of a name. Any race which is sadistic enough to name their young one Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtseva must necessarily be a depressed one. Their tragedies must necessarily be complex and detailed and heroic and there must necessarily be a complete lack of trivial subject matters. The trivial subject matters are for races which name their children Tom and Rob and Dick. For such races, human life is a travesty to begin with, their coffers have always been full and they have never had to face paucity as a culture, hence, their literature is light on its feet. Imagine an elaborate tragedy with backstabbing siblings and cheating wives and death and misery and moral turpitude and imagine its central character named Bob. Just doesn't cut it. Something tells me that that central character can only be named Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov or some other Russian derivative of the same. Well that's my alternative 'god' theory of the difficulty of Russian literature. It kicks in when I don't feel like thinking or arguing because it's all quite pointless to begin with. There is never a resolution to any argument so I might as well have a bit of fun and indulge in a bit of mockery - very much like the god argument. Did I make any sense? Oh dear god, I sincerely hope not!

Let there be humans...

Posted by Ankit On January 17th, 2010

I was talking to MV about evolution and he recommended a Nat-Geo documentary titled 'The human family tree' for me to watch. To anyone who is interested in knowing about the origins of us humans in a lucid and interesting way, I would also recommend this highly engrossing documentary.

I have an intense peeve against most of my teachers during my early formative years, a trait that they share with an overwhelming majority of all teachers - they were either too incompetent or too inconsiderate. The fact that they could make 'acquisition of knowledge' boring is almost too difficult for me to comprehend now. Biology, for instance, is a subject that I remember with a special hatred but I also realize that my boredom with it was more a result of how it was taught rather than what was taught. Despite all my formal education then, I have managed to save 'curiosity' from the deathly throes of uninspiring teachers. And I have lately become curious about the origins of humans and what legacy we share with other creatures on Earth. That science decodes the labyrinthine links and interlinks between all existing living organisms today with the help of genetic studies, fossil records, and radioactive dating is fascinating in itself, but I'm more thrilled by what they have found.

Mitochondrial DNA is one of only two parts (The other is Y-chromosome) of the genome which are not shuffled around by evolutionary processes. It gets passed down the generations unchanged. It is amazing that every single one of us 6.7 billions living humans has the same Mitochondrial DNA - one that they have inherited from a woman who lived in Africa about 160,000 years ago. She has been termed the 'Mitochondrial Eve' and is, in some sense, the scientific mother of all humans alive today. Her descendants, in what is termed as the Out of Africa theory, left Africa for the first time around 60,000 years ago and moved on to populate the rest of the world. Starting from Middle-East, South Asia was colonized 50,000 years ago, Australia and Europe by 40, and East Asia (Korea and Japan) by 30, and North America by 16,000 (although this last date is controversial). In their quest for territory, our direct ancestors met the already existing species from the Homo genus like the Homo Erectus and Neanderthals and did to them what we are naturally good at doing - annihilation. I find it amazing to think that most of our early literature which is religious and mythical in nature and derives inspiration from otherwise ordinary battles and natural phenomena concerns but a minuscule fraction of the total human experience. Imagine how much more rich our history and our culture would have been, if only it had the resources to tap into the thousands of stories of hardships and courage that must dot our existence during the last 200,000 years.

Then again, the last 200,000 years is nothing but a slight flutter in the larger story of evolution of life on Earth. It is often naively suggested that we have descended from monkeys. The truth is that all the living species, both animals and plants, are cousins and not one of them has descended from the other. And in this family tree, the closest cousins to us modern humans are Chimpanzees and Bonobos, and the common ancestor to all 3 of us lived about 5 million years ago in Africa. It was a bit like humans and a bit like Chimps but nowhere like monkeys (it had no tail). So our branch of the family tree joins Chimps and Bonobos at 5 million years from now. This combined branch joins Gorillas in Africa at a common ancestor who lived 7 million years ago. This branch of our common ancestor joins the common ancestors of Orangutans at about 14 million years ago in Asia! Gibbons join us about 18 million years, and it is only if we go back 25 million years ago that we find the common ancestor who gave birth to all apes including us and so called Old World monkeys like langoors and baboons.

Ancestors of other species join us as we keep going back (New World monkeys at 40 mya, Tarsiers at 58 mya, Lemurs etc. at 63 mya) and we finally reach the K-T boundary - 65 million years ago. There is a thin layer of Iridium present all across the world at a depth in the Earth's crust which corresponds to a time 65 million years in the past. While Iridium is rare in Earth, it is common in meteorites. The Chicxulub crater is a titanic impact crater - 100 miles wide and 30 miles deep - buried below the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico and it has been dated at 65 mya. And the last fossils of terrestrial dinosaurs date back to 65 mya. It was only after the K-T boundary that the age of mammals began when their dinosaurial predators went extinct. It is weird to think that had that meteorite not impacted the Earth and wiped off the dinosaurs, humanity might not have had the chance to begin. On that fateful day 65 mya, all of our ancestors all across the world most probably went deaf and blind from the catastrophic impact, and were hanging in there by the skin of their teeth - all they could perhaps manage was to live long enough to reproduce - but that was enough...

If you really think about it, even 65 million years is but a small drop in the ocean of galactic time. As someone very smart once said, 'humans are what happens when you give 14 billion years to the hydrogen atom.'

Elementary, Dr. Ankit

Posted by Ankit On December 13th, 2009

So now that I'm allowed to officially add the prefix of Dr. in front of my name, it would be interesting to look back and evaluate the 4 years which culminated in this title. Because we do not do it often, stages of our lives which are like liquids of different densities often merge into puddles of muddy water when inspected under the lens of inaccurate reminiscences. And it is for this reason that I want to 'ankit' or inscribe my impressions of this very important temporal chunk while the memories are still sharp around the edges and their flavor still spicy at the tip of my tongue.

I remember a Friday evening, much like many others, in visions of blurred lamps, svelte waitresses, sumptuous portions, and intoxicating aromas, in a Mexican restaurant in La Jolla downtown; I was sitting with some friends and someone asked a general question to the effect of, 'which were your most satisfying/memorable years?' In the gushing spring of romantic nostalgia, my friends remembered their school times and college times with sad, hollow eyes fixed into the distance, as if trying to grope for a memory hopelessly lost to the brutality and crudeness of passing time. I remember being disconcerted to find that I was the only one who rated my time doing the Ph.D as the most memorable. This is not to say that I don't remember my earlier years with fondness but if the metric of one's life's worth is how much one has grown as a person as a consequence of the various experiences one is subjected to (which is probably the most important metric for me) I would be hard pressed to think that my cocooned, illiterate, spoon-fed earlier time would rate higher than the more recent one. Yes, there is a lot of nostalgia involved, and if someone were to ask me during one of those infrequent periods of depression, I would probably crave for the innocence and simplicity of the times when chocolates cost a fraction of a dollar but in saner times, I realize that it is better to live with the realization of satisfaction and the knowledge of a changing person (hopefully better) than just being happy in hindsight. And it is scaringly easy to get bottled up into a sedentary useless waste of the gift of human intelligence - one just needs a TV with a cable connection, a remote, and a couch. In a world infested with the perils of easy comfort and blessed with a body which has an evolutionary inclination to avoid all risks/experiences once the basic necessities of survival are met, I feel happy that I was able to keep alight a slight flame of adventure and curiosity. Mnemosyne, in her supple grace, fills me with pride with images of 150mph on my motorcycle's speedometer, golden gate's deck in fog, distant sands on the bank of La Jolla shores, graphite streaks on paper, discordant notes of ivory and ebony, intellectual satisfaction of being the temporary but sole possessor of a secret of physical reality, and of having had relations with vibrant interesting people.

I am happy that somewhere along the way I ditched religion and understood, within reasonable bounds of uncertainty, that it is a sham of massive proportions, no better than other frauds which exploit human gullibility and his need for 'believing' like homeopathy and other 'alternative' balderdash. The skepticism and cynicism which came with reading masses upon masses of mediocre publications at least instilled enough intelligence for me to realize when a really stupid person is bullshitting. But it has not yet instilled enough intelligence for me to call out on the bullshits of smart folks. Richard Dawkins might be making things up, Nabokov might just be horsing around - I realize that I am yet not intelligent enough to know but I at least have the doubt which lacks in a 'man of faith'. I like to think of life as a long and winded struggle for demanding more and more intelligence from those who are smart enough to swindle you. It's the least that we simple people can do for our own intellectual ego. What is important is to have that doubt and I owe this doubt to the last 4 years which saw innumerable discussions with some really intelligent friends, and painstaking but ultimately enjoyable and humbling studies in physics, intelligence, evolution etc.

At the cost of sounding immodest but at the demand of honesty, I would have to say that the journey en route to the Ph.D was never too stressful. It might be attributed to an easy going adviser but it should not be attributed to mediocre work. And the fact that I liked bits and pieces of the work a lot made it all, quite uncharacteristically for a grad student, memorable.

Yes, it was a memorable trip, the last 4 years. In its white watered wake, I have lost most of my friends and relatives. When I stand aloof on the quarterdeck and look down into the turbulent waters of the past, I see them in vaguely recognizable images of camaraderie - the distance separating us is not just temporal but is made of a fundamental difference in outlook, which is not to say that one's is better than the other but that they are different. But this is a chasm which is probably harder to cross than any other. So I stand on the quarterdeck and instead raise my gaze to the beautiful horizon, the artist's horizon. The Sun will go down in a few moments, completing a chore it has kept doing for the last 5 billion years in a universe that has existed for a few more. I get lost in the vastness of it all and the next obvious question of the meanings of our lives and contributions. There are visions of enormous explosions across mindboggling scales until the first bacterias take breath in an insignificant part of the inhospitable world. They replicate and mutate across ages and give rise to the first humans about 200,000 years ago. And in another 200 millenniums these humans are closer than ever to understanding what the holy fuck happened! If this quest is not grand then what is? It is made up of small contributions from different individuals across centuries. The simple beauty and ultimate purpose of wanting to understand how the world ticks. I am happy to have made a very small contribution in this grand scheme of things - not related to elementary physics yet furthering our understanding of a small subset of physical reality... Good times, surely.

Dissertation woes

Posted by Ankit On November 3rd, 2009

Oh blast! This thesis writing business is really beginning to rile me up now. Because, you see, it's a whole lot of charade to begin with. Like any sort of bookkeeping, because that's what it really is, it's one daunting, limitless ocean of morbidity that is wetting my feet as I take my first steps with the intention of wading across. And to reach the land on the other end, I have but a skiff with a spatula for the oar. There is no humor involved and I am not allowed to make it interesting. I cannot write sentences like, 'While the academic world was nestling in the arms of its own complacency, it was hardly aware of what was brewing in one man's mind.' I have to be chronological and am not allowed to keep the best for the last - I cannot build it all up towards one nerve racking, palpitating sentence, 'Yes, my dear Mr. Hamilton - you've had it all wrong. Please have a seat for the shock of it all may be too hard for you to bear.' There is no room to exaggerate, to metaphorise, to embellish, to dream, to give voice to the passion that one does indeed feel sometimes in academic research.

In the golden lightning

of the sunken sun,

O'er which clouds are bright'ning

thou dost float and run,

Like an unbodied joy whose race has just begun. (-P.B.S.)

No, I am not allowed to do any of it. Rather, I must worry about how to expand the amount of my work so that it at least appears as if my last 4 years have not been completely squandered. At 66 pages currently, and with hardly a hope of going beyond 150 (doublespaced mind you), my contribution hardly appears a gushing spring of knowledge. It's more like a gentle, dying trickle from a broken tap in the middle of a parched desert. And Masters students routinely clock 200. I think I'll have to fiddle with the spacing, and tinker with the font, adjust the margins, and tamper the text in order to post such gallumphing figures.

Maybe I am exaggerating but that is one peeve that I have with the whole process of 'growing up'. There is something behind this that I feel strongly about and often feel saddened by. It's that we do not exaggerate often and well enough as we grow up. This ability of making things up from thin air, adorning it with beautiful false ideas, coloring it with dazzling deceitful colors, it not only leaves us to some extent as we grow older, it also suffers as we develop a condescending attitude towards it. And as this vitality shrinks within, we are left predictable, and immobile, all our ideas fossilized into useless sediments - just reminders of times gone by. And some of us go on to produce Ph.D. dissertations so bland, it's more fun a watch a glacier melt.

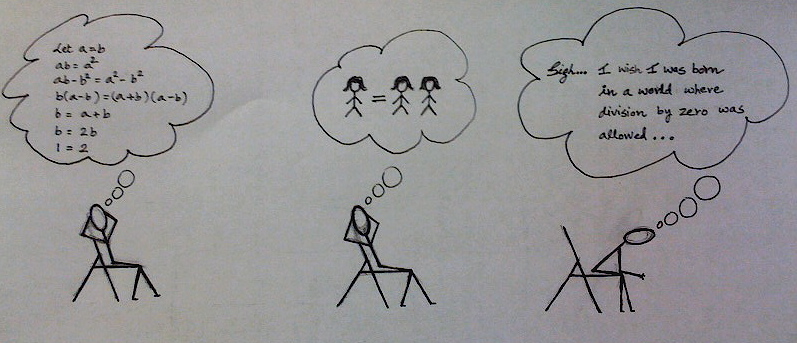

Division by zero

Posted by Ankit On October 22nd, 2009

...and it would be a crazy happy world. Truth would only be a matter of one's imagination. Fallacies would be the only consistencies and no professor would be smug. People would be generally confused and disoriented and no one would bat an eyelid when sold 5 oranges after paying for 6. It would be a chaotic world with its unsure zombie like citizens walking around on crazy Mobius strip shaped roads. The principle of mutually assured destruction would cease to exist because no one would be sure if 10,000 is greater than 1. Hence countries would stage preemptive nuclear strikes and finish off this stumbling, hobbling world and the rest of the universe wouldn't give a damn.

But there would be advantages, definitely. If somebody asks you what would you do if you had a million dollars, you can simply say that you don't even need a million dollars. And yes, quantum electrodynamics would probably have a believable premise.

In support of voyeurism

Posted by Ankit On October 12th, 2009

I sometimes get this weird idea that voyeurism should not be seen as the evil that it is often seen as. I often get such ideas when I am sitting in a dimly lit balcony looking at the apartments in the front or when I am walking on the street and the dark night is hindered by columns of well lit miniaturized windows. It is a mistake to link the innocent pleasures of a voyeur with a necessarily sexual motive. Often, they are quite innocuous. We are naturally curious about other people. Maybe in their imperfect existences we try to find some personal solace; maybe in their picture perfect harmonies, we try to forget our own dissonances. Personally speaking, I find the act of looking at a set of lighted apartments mystifying and intriguing at various levels. To think that I am able to look at these people with a vantage point that none of them will ever be able to take advantage of is exciting enough. There those people are, hardly aware of their neighbors, going about their businesses with a robotic monotonicity, and yet I can see them as part of a bigger picture. By being a voyeur, I can place them in the objective, geometric description, and realize that even at a scale as small as a few apartments, there is not much to differentiate them, nobody is particularly special. I understand that they have their hopes and their ambitions, their pains and insecurities, but for now, this is merely a figment of my own imagination, solely a theoretical possibility. But as is often the case, it is imagination which trumps reality, and I ascribe to them emotions that they might never have and lives of such beauty and intricacy that reality often fails to provide. And all of this grandeur, all of these subtle possibilities, such brilliant color, all of it is neatly tucked into a set of some lighted rooms and a few mundane details. Their cozy little existences, indifferentiable from their neighbors, captures my imagination with both their periodical, repeatable, matchbox like boredom, and the dazzling potential that lies within. I find it amazing to think that each little yellow dot on tall skyscraper contains within itself so many experiences, mistakes, glories, hardships, hope, despair, so much life...

And sometimes, if you are really lucky, your voyeuristic disposition might help solve a grisly murder!

GEB

Posted by Ankit On September 2nd, 2009

After days of diligent pouring, I have finally waded across 750 pages of paradoxes, logic, philosophy, mathematics, painting, music, and computation and crossed the checkered flag signaling the end of Hofstadter's 'Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid.' Why, you might ask, is this important? Well, in the field of 'intelligent, thought provoking books', GEB has a towering, almost bullying, presence. It is the Don Bradman of 'intellectual' writing. Consequently it manages to scare off the reader even before it begins, partly owing to the lofty goals it sets out in the beginning, and partly because of the sheer thickness that requires negotiation. And now that I am done, I at least want to jot down some of the ideas which have managed to stick, for the fear of losing them again.

What is it about? For a book that deals with issues as different as molecular biology and transcendental music, it has a surprisingly clear and single minded focus. I wonder if anyone who has read it finds that the book is about anything but one single sentence and its ramifications. Epimenides paradox is the sentence:

'This sentence is false'.

No matter how much you think about it, it won't make sense. There is something deeply sinister and pathological about the sentence. But it's just language and language can be easily pushed under the rug. It doesn't bring the house down. GEB primarily tells the story of this dude called Kurt Godel who devised a way of applying this sentence to mathematics in the first half of the 20th century. He showed that for a sufficiently complex formal system (like number theory) there is a way to formulate a theorem which is true in that system and which says:

'I am not a theorem in this system'.

In other words, he proved that a mathematical system which aims to be consistent (no self contradictions) will not be able to provide proofs for all that is true within that system, and that a system which aims to give proofs to all truths within it is necessarily inconsistent. If you think about it, a result of this depth does indeed require a 750 page tome to talk about it. I mean, results and theorems in every other discipline are merely humanity's tentative, though increasingly accurate, stabs in darkness. They do and will continue to suffer from our own sensory limitations. Experimental validations of our grandest astronomical theories and minutest quantum ones are merely smudges on photographic plates. On the other hand, theorems in mathematics stand alone, almost inviolable (almost). And a theorem about how mathematics can and will behave should truly count as the towering achievement of human intellect. It should also be seen as one of the greatest contributions to society because mathematics is the language we have chosen to interpret the world in. It is the only tool we have got and it is precisely because of it that society affords us the comforts and leisure which allow us to indulge our creativities, and be sympathetic towards fellow humans, animals, nature.

The book goes on to study the implications of the theorem and its curiously self-referential nature on issues like the mysteriousness of the human mind, the future of artificial intelligence, the meaning and emergence of truth and beauty in artistic creations, the existence/nonexistence of free will, the illusion of intelligence resulting from a system of sufficient complexity, genetic evolution etc. The scope of the book is breathtakingly broad and the fact that Hofstadter makes it all appear coherent is either because he is a depressing genius in deception or because deep down, things should be so. Like Hardy mentioned about Ramanujan's crazy results: 'They must be true because, if they are not true, no one would have had the imagination to invent them.'

I found that the book, despite its content and size, is cheerfully lucid. It has the same 'philosophical displacement' as David Deutsch's 'The fabric of reality' but while Dr. Deutsch assumed that all his readers trace their route back to Einstein and decided to cram everything in 200 pages, Hofstadter is more sympathetic to our vacuity. He has included fictional dialogues between Lewis Carrol's characters Tortoise and Achilles which give a simple-worded, though cryptic, overview of the ideas. And he has shown elaborate harmonies between mathematics, painting (M.C.Escher, Rene Magritte) and music (J.S.Bach) to sustain a general curiosity. But then, he hasn't done all this for the express desire sustaining interest. He has done it because, as you start feeling by the end of the book, there is a very deep connection between such disparate fields. It shouldn't come as a surprise that what we find harmonious in music and beautiful in art, often has deep mathematical associations. When music is bound in meters and beats, and art has familiar geometries, when poetry is enclosed in metered iambs, it seems that a condition for beauty is automatically met. This, as opposed to postmodern art, aleotoric music, which, in order to explain their significance, have to invoke ideas of rebellion, boredom, authority and conformity. Where such deep connections exist between mathematics and art, it is interesting to see how something as profound as Godel's Incompleteness and self-reference commute between the two. And this is what GEB explores, with humor and intelligence.

On the road

Posted by Ankit On July 14th, 2009

I have been reading a lot lately and the latest book I completed is this gem of a work called 'On the road' by Jack Kerouac. His language is strangely evocative and his stories glow with the sad eyed glimmer of unachievable freedom, they are resplendent with the strange sounds of gay abandon. Underscoring his amphetamined recollections of jazz, bars, girls, drugs, and travels in the bleary swathes of 50's America, what shines clear and foremost is his zest for life, humanity and the country he loved so much. But more importantly, on a personal level, it is yet another reminder to me that it is the ugly, depraved, debauched, and irreverent (not in a hugely antisocial way) side of man which is infinitely more interesting and pregnant with creative possibilities than the law abiding, sheltered, devoid of any worthwhile experiences side. Kerouac describes it as,

'But then they danced down the streets like dingledodies, and I shambled after as I've been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes 'Awww!"

His prose, at places, is positively fabulous. Words follow each other with nonchalance while magnificent, almost tangible ideas and visions take shape in the background. And the result is an image which is not just supremely beautiful but also seems like the only natural image for the situation. It's, for example, not just the description of a carpet but the carpetness incarnate. He describes the view from Golden Gate in SFO as,

'There was the Pacific, a few more foothills away, blue and vast with the great wall of white advancing from the legendary potato patch where Frisco fogs are born. Another hour it would come streaming through the golden gate to shroud the romantic city in white, and a young man would hold his girl by the hand and climb slowly up a long white sidewalk with a bottle of Tokay in his pocket. That was Frisco; and beautiful women standing in white doorways, waiting for their men;'

It is a peaceful, even a contented vision. A vision he is able to conjure not by being blatant about it but by the repeated use of 'white', a color that is automatically tranquil. He ends with the beautiful lines,

So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars'll be out, and don't you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what's going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty.'